Faith leaders who minister to Christians in Venezuela and the Venezuelan diaspora in the United States are urging prayers for peace as they attend to congregations roiled by uncertainty and high emotions following the U.S. capture of deposed leader Nicolás Maduro.

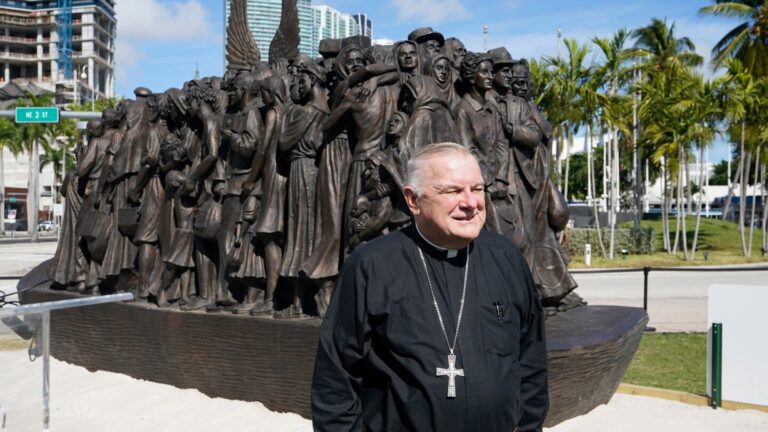

In Venezuela, initial statements from the Catholic bishops’ conference and the Evangelical Council of Venezuela were cautious, appealing for calm and patience, while many pastors in the diaspora welcomed Maduro’s ouster. The Catholic archbishop of Miami, who ministers to the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., said there is an anxiousness about what is next, but he believes the church has a key role to play in helping the Catholic-majority country move forward.

About 8 million people have fled Venezuela since 2014, settling first in neighboring countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. After the COVID-19 pandemic, they increasingly set their sights on the United States, walking through the jungle in Colombia and Panama or flying to the U.S. on humanitarian parole with a financial sponsor.

Many have settled in South Florida, where they make up the country’s biggest Venezuelan community. Community members took to the streets waving flags in celebration after Maduro and his wife were captured in a U.S. military operation on Saturday.

But some have mixed feelings, Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski said. Since the start of February, the Trump administration has ended two federal programs that together allowed more 700,000 Venezuelans to live and work legally in the U.S.

“People are happy because Maduro is out, but there’s still a lot of uncertainty,” Wenski told The Associated Press in a telephone interview.

“As far as for those who are here in this country that have lost their temporary protective status, they’re anxious about returning unless there is a real change of the political and social situation in the country.”

Archbishop says the Catholic Church has a role to play

Amid the rising uncertainty in Venezuela, interim President Delcy Rodríguez has taken the place of Maduro and offered to collaborate with the Trump administration in what could be a seismic shift in relations between the adversary governments.

Wenski said he hopes conditions for the Catholic Church in Venezuela improve now that Maduro has been ousted.

“There have been over the years great tensions between the Maduro and Chavez regimes with the Catholic Church,” said Wenski, referring to Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez. “And still, in Venezuela, the church is perhaps the only institution that is independent of the government, that can speak quite courageously about the situation in the country.”

Among the tensions between the Maduro administration and the church, Wenski recalled how Cardinal Baltazar Porras, the archbishop emeritus of Caracas and a critic of the Maduro government, recently had his passport confiscated by Venezuelan immigration officials and was banned from traveling abroad.

“I think that the church should continue to speak up for democracy, but at the same time be patient, to be calm,” Wenski said. “The church is always promoting reconciliation and certainly given the polarization in Venezuela over these years … the church has to be a voice urging reconciliation between the different factions and the different political opinions or political parties in the country.”

In Doral, a Miami suburb of 80,000 that has been nicknamed “Little Venezuela” or “Doralzuela” because of its large Venezuelan population, many prayed for the future of their native country during Sunday services a day after Maduro was captured.

The Rev. Israel Mago, the Venezuelan born-pastor of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Doral, told worshippers to pray for “a fair and peaceful transition in Venezuela, so peace and justice can reign.”

At the end of the service, he invited the congregation to join him in a special afternoon vigil to pray for justice in their countries of origin, especially, he said in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua, where human rights advocates, exiled priests and the U.S. government say the Nicaraguan government is carrying out a crackdown on religion.

Pastors and the faithful turn to prayer

Also in Doral, the Rev. Frank López of Jesus Worship Center started his Sunday sermon by “congratulating” the Venezuelan people and thanking God for President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

“It’s time that in America, starting with Venezuela and may it continue with Cuba too, the glory and freedom might be manifested that Christ bought for you, for me, on the cross at Calvary,” the evangelical pastor told the cheering congregation, which counts more than 3,000 members from over 40 different nationalities.

In Philadelphia, members of the Venezuelan community gathered for a special Sunday service at the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul. Many carried Venezuelan flags and prayer beads or wore jerseys of the national soccer team. The gathering was organized by Casa de Venezuela and other Venezuelan nonprofits in the U.S.

“We wanted to do it at the church so people would feel comfortable, protected. And this is regarded as a space of reconciliation,” said Arianne Bracho, vice president of Casa de Venezuela Philadelphia.

As a baptized but nonpracticing Catholic, she still felt compelled to pray for her country in a service that she described as emotional. “This was a gathering to reaffirm our hope, our faith, to call on tranquility and calm. And I think the house of God, whichever religion it might be, is the right place,” she said in Spanish.

Most of her family, she said, has been living abroad across the world, from “Japan to Colombia,” due to the political and economic crises in Venezuela. Today, she feels conflicted emotions about the country’s moment.

“I’m convulsed; I have mixed feelings. It was tough seeing our country being bombed. But it was necessary to remove Maduro for his drug crimes and human rights violations,” she said.

“What was clear to me, on that day where we gathered at the church, is that we all have faith that this will end.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.